William Faulkner’s “Light in August”: a Great (American) Novel.

She begins to eat. She eats slowly, steadily, sucking the rich sardine oil from her fingers with slow and complete relish. Then she stops, not abruptly, yet with utter completeness, her jaw still in midchewing, a bitten cracker in her hand and her face lowered a little and her eyes, blank, as if she were listening to something very far away or so near as to be inside her. Her face has drained of colour, of its full, hearty blood, and she sits quite still, hearing and feeling the implacable and immemorial earth, but without fear or alarm. ‘It’s twins at least’, she says to herself, without lip movement, without sound. Then the spasm passes. She eats again. The wagon has not stopped; time has not stopped. The wagon crests the final hill and they see smoke.

William Faulkner has the innate capability to introduce his characters through their actions in such an exceptional way that they remain forever imprinted on our minds. This appears clearly in ‘The Sound and the Fury’, (see my previous article here), where each member of the Compson family stands out with its specific and distinctive voice and plays a role in the decline and fall of the family. In ‘Light in August’, instead, Faulkner’s characters are not related by blood, but their destiny becomes, unavoidably, intertwined – shaping the development of the dramatic plot.

In the passage above, there is everything we need to know about Lena, the first character we encounter. We understand her mild but determined nature, and we soon acknowledge the naïve but absolutely charming beauty of her soul (coming to my mind is Kent Haruf’s Victoria Roubideaux, in ‘The Plainsong’, as a modern representation of Lena. Both pregnant girls attract people’s empathy, are alone in the world and staunchly believe in the power of love.). Due to this quality, people are willing to help Lena, who holds the absolute certainty that she will eventually find her baby’s father (Lucas Burch). The man ‘supposedly’ left her to find a better job, but in reality has no intention to come back to her. She refuses to consider him a charlatan and repeats her story to everyone ‘with that patient and transparent recapitulation of a lying child’. Therefore, with true determination, she decides to find Lucas and travels long distances, first walking, and then, eventually, hitching a ride to Jefferson, Alabama, where it seems that someone has finally spotted Lucas working at the planing mill. In reality, the worker’s name is Byron Bunch and not Lucas Burch, who in the meantime has renamed himself Joe Brown. Byron Bunch, the good soul, will ultimately have a great role in ‘saving’ Lena.

While following Lena’s quest for her man, we encounter the main character, Joe Christmas. In a passage reminiscent, in terms of style, of ‘The Sound and the Fury” Faulkner introduces his past: ‘Memory believes before knowing remembers. Believes longer than recollects, longer than knowing even wonders…’, and crafts an anti-hero of magnificent proportion. As I read the novel and found out more about Joe’s complexities and enigmatic personality, about his ‘naturally’ evil nature and resentment towards the entire world, I couldn’t help but seeing him as the absolute nemesis of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin in ‘The Idiot’, a character with the purest soul, which embodies the Christian ideal of beauty.

Joe Christmas (impossible not to think of the symbolism of ‘Christmas’ as Jesus’ birth and ‘J’ of Joe and Jesus as well) gets involved with Miss Burden, a very intriguing female character. She is a reclusive resident of Jefferson, where her family relocated to the South after the Reconstruction. Her grandfather and brother supported voting rights for blacks and were killed by a local man. It is rumoured that Miss Burden prefers having sexual relations with black men. Therefore, she is immediately attracted to Christmas, who is a black man ‘trapped’ in a white-skinned body. The enigma of his origins, of which he himself – being an orphan – is no certain, and the ambiguity of his race, introduce the theme of racial discrimination and partly explain Christmas’ anger towards the world. It is also interesting to note that Christmas cherishes his ‘hidden blackness’. He would watch ‘his white chest arch deeper and deeper within his ribcage, trying to breathe into himself the dark odour, the dark and inscrutable thinking and being of negroes, with each suspiration trying to expel from himself the white blood and the white thinking and being.’

It is difficult to see him as a martyr because of the racial implications and his being discriminated, since he chooses violence always and in any case and feels contempt for humanity. His lack of identity, his past as a child abandoned at the doorsteps of an orphanage (by someone of his own family, as we will later discover) and then adopted by a ruthless man, and his inability to find a home ‘somewhere’, leave him as a restless wandering soul with the need to inflict harm on others, and therefore condemned to Hell. A skilled manipulator in his relationship with Miss Burden, he comes and goes from her house as he pleases. On the other hand, she never loses hope to ‘rescue’ him and save his soul, to the point of dependence and obsession. ‘And she would listen as quietly, and he knew that she was not convinced and she knew that he was not. Yet neither surrendered; worse: they would not let one another alone; he would not even go away. And they would stand for a while longer in the quiet dusk peopled, as though from their loins, by a myriad ghosts of dead sins and delights, looking at one another’s still and fading face, weary, spent, and indomitable.’ It is ironic that this sense of charity and desire to help and save Christmas will in reality be Miss Burden’s condemnation.

Faulkner is interested in the outcasts, the misfits, the fallen and marginalised characters, full of contradictions and yet – for this reason – so well-rounded that they all stand out. Joe Christmas, Reverend Hightower (despised by people and forced out of office after the death of his promiscuous wife), Joe Birch and Miss Burden are all loners and isolated people trapped by their past, each of them with their own quest.

In terms of writing style, Faulkner takes us back and forth, through the past and the present, but in a much more accessible way if compared to ‘The Sound and The Fury’. Like in a cycle, the main theme of the wandering souls (Lena, the positive one) and Christmas (the negative, unfulfilled one) is what drives the story. At the same time, the chorus of voices and the development of events act as a corollary to this circularity.

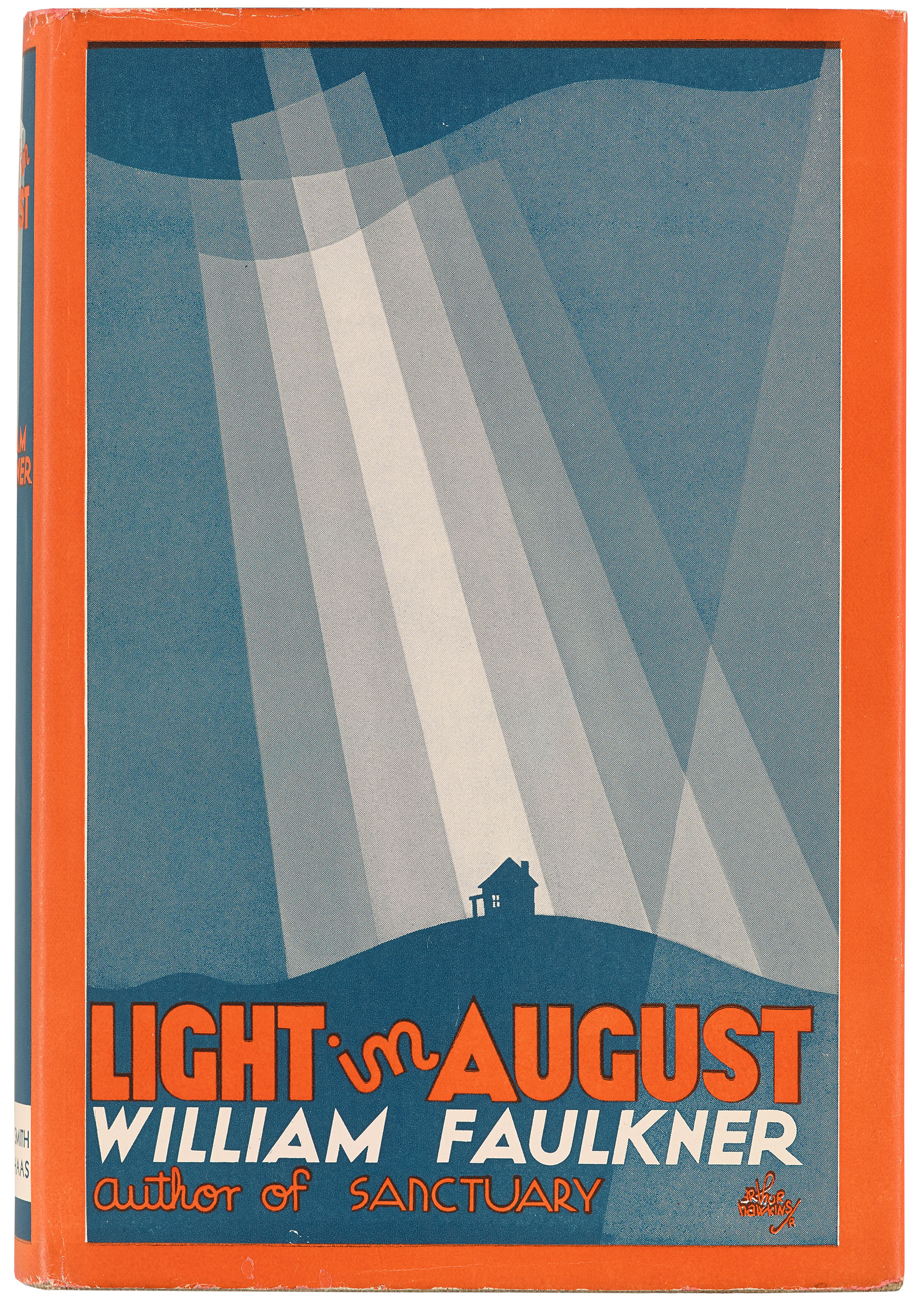

The light in August is the fire at the Burden house, but also the cleansing from tragedy and violence that paves the way for the new life that Lena carries within herself. Lena is the light, the beacon of hope capable of overcoming her past and look at the future with simplicity and pureness of spirit.

For the reader, the ‘Light in August’ is, indeed, the glaring beauty of this work, a great, fine novel. It is, definitely, very American, first and foremost for dealing with the concerns about race, class and religion, especially in the American South. But it is also relevant to us all, and still very modern, despite being published in 1932. The power of the past, free will, identity, religiosity, the conundrum of race, and the draw of female sexuality are all themes that resonate with mankind now as they did eighty-six years ago, and not only in the United States.

Paola Caronni